Women’s tears have been a subject of ridicule for alpha males, but turns out it is exactly for those brutes that tears evolved, writes Satyen K. Bordoloi.

At an all-women’s filmmaker panel in the 2010 Mumbai Film Festival, filmmaker Zoya Akhtar was unapologetic about her mood swings during her periods, saying: “On my sets I will cry if I want to. I will be in all my hormonal glory. As a man, you have chosen to be part of my set, so you handle it, boy.” Back then, before the full manifestation of women’s power, we saw in the second half of the decade, this was seen as bold and brazen.

What Zoya did not know, and neither did anyone else back then, are the evolutionary reasons for women’s tears. In a recent study published in PLOS Biology, a team of researchers from Israel and the United States investigated whether women’s tears can influence men’s aggression. The idea for this came from rodent studies, where it was observed that their tears carried chemical signals that reduced aggression in other members. The scientists wanted to see if tears are a mammalian-wide mechanism that provides a chemical blanket protecting against aggression

The findings were most unexpected.

(Image Credit: Journal Information | PLOS ONE)

SNIFFING TEARS:

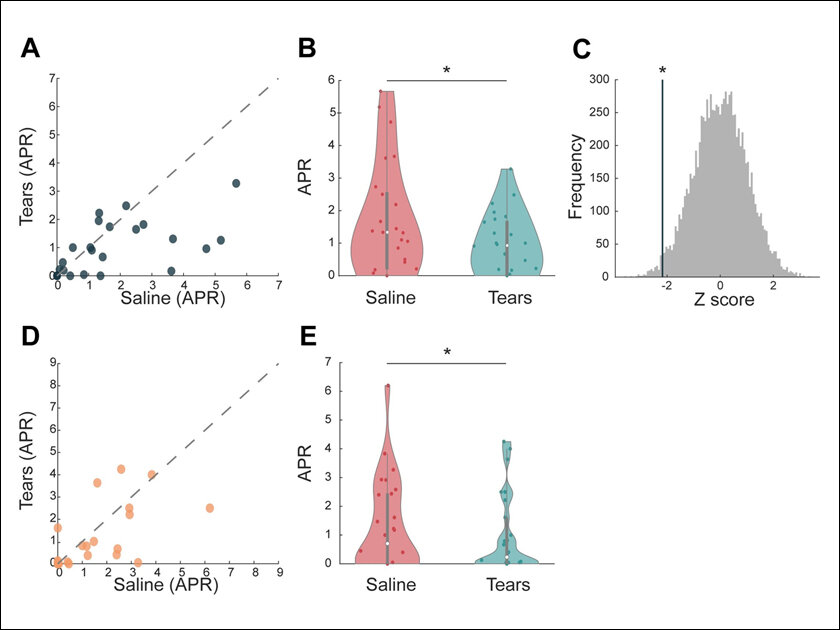

To test the hypothesis, the researchers conducted a series of experiments using behavioural, perceptual, molecular, and neural methods. They collected tears from women who turned emotional while watching sad movies. They then asked male volunteers to sniff either tears or saline, without knowing what they were smelling and measured their aggression levels using a standard behavioural test.

This involved playing a competitive game against another person, in which the winner could punish the loser by administering an unpleasant noise. The intensity and duration of the noise chosen by the player reflected their level of aggression. To rule out sexual arousal from the results, the researchers also measured the players’ testosterone levels, heart rate, and skin conductance.

The results showed that sniffing tears significantly reduced men’s aggression – by 43.7% – compared to sniffing saline. This effect wasn’t due to changes in arousal, as no differences were observed in those factors. The effect wasn’t due to changes in perception either, as the men could neither detect any odour nor identify the source of the stimuli.

(Image Credit: Journal Information | PLOS ONE)

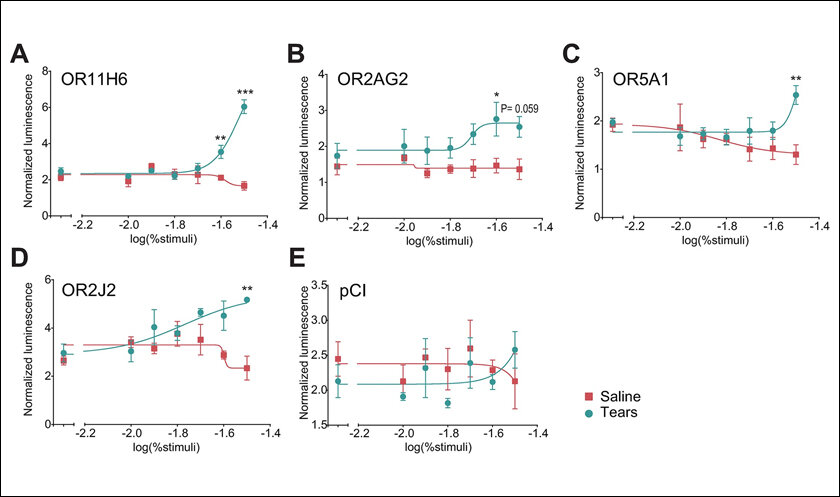

The researchers did not stop there. To further explore the mechanism behind this effect, they applied tears or saline to 62 human olfactory receptors (proteins that detect odours) in a test tube. They found that four receptors responded in a dose-dependent manner to tears, but not to saline, suggesting that tears contain a specific chemical signal that activates these receptors.

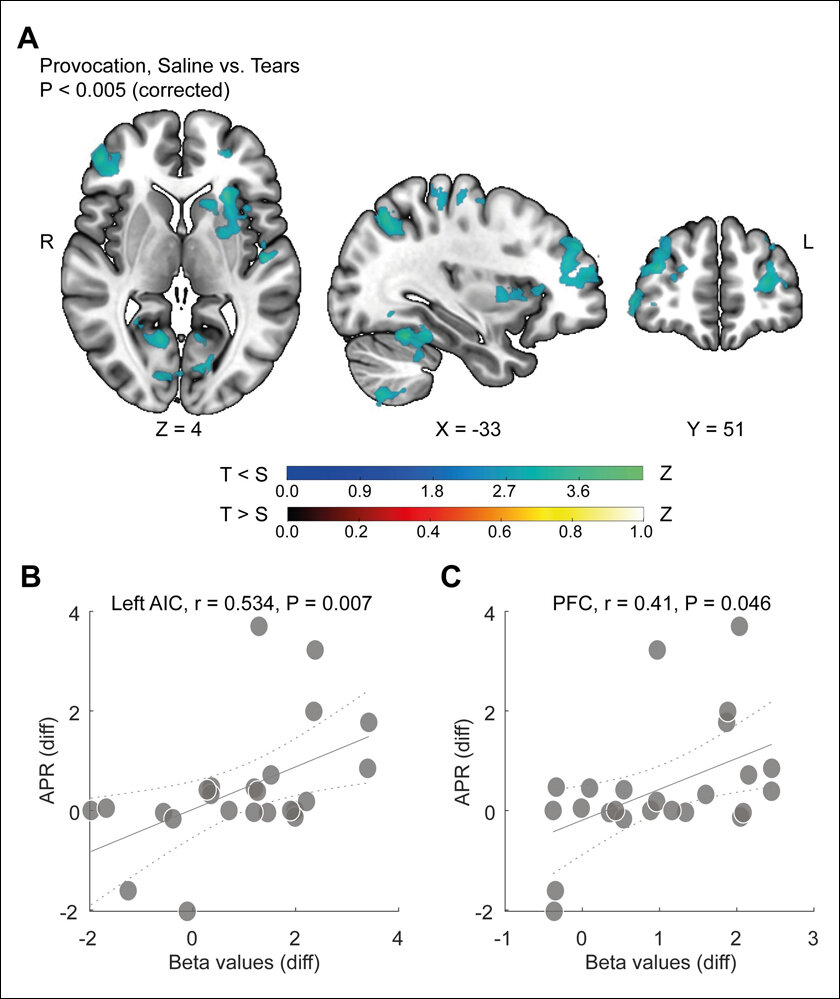

Finally, to examine the brain regions involved in this effect, they repeated the experiment while scanning men’s brains using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). They found that sniffing tears increased the connectivity between the neural substrates of smell and aggression in the brain i.e. the olfactory bulb, the amygdala, and the hypothalamus. This means tears modulated communication between these brain regions, resulting in lower levels of neural activity in the areas connected with aggression.

Taken together, these findings suggest that women’s tears contain a chemical signal which, though odourless, can reduce men’s aggression by activating specific olfactory receptors and altering the brain network involved in aggression. And, this is not unique to humans. The same effect has been observed in rodents, implying that tears are a common evolutionary adaptation that helps regulate social behaviour among mammals.

WHAT THIS STUDY MEANS:

In the paper, the researchers speculate that tears may have evolved as a way of signalling vulnerability, distress, or appeasement, thus helping in preventing or resolving conflicts. They also suggest that tears may have other effects on social behaviour, such as enhancing empathy, trust, or cooperation, which, hopefully, they or someone else will explore in future studies.

You must have heard this argument from many an alpha man: seeing a woman’s ‘unreasonable’ tears, he quietened down because it was pointless to fight then. The implication was that it was the man who was magnanimous. This research proves that the opposite is true. It is the woman who thought the man was being unreasonable. Hence, to avoid further conflict which would not resolve and might cause her harm (ask any victim of domestic abuse) she shed tears to quieten the man with neurotransmitters to avoid further conflict. Of course, the women didn’t know they were doing this either. Now they do.

To some, this study might be frivolous. But what we do with it, could have profound implications on how society functions. If we could figure out the compounds in tears that help tone down aggression, we could manufacture them in a lab. Thus, in the future, instead of tear-gas to disperse a crowd, perhaps they’ll be blasted with water mixed with these compounds to modulate the crowd’s aggression and violence. And what about men who have anger management issues? Could they carry bottles of these chemicals and sniff them to control their aggression?

This could also help us understand the role of emotions and their expressions in social interactions. Who knows, they might even explain the many unexplained arcs of history. As the knowledge of this study spreads, researchers constructing historical records could now keep another factor in mind while they piece together the past: not just the role of women, but their strategic tears in stopping, or in manipulative women – starting, conflicts.

LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY:

Women naturally will be excited by this study, that something they were criticized for, has a purpose to it. But before ladies and progressive gents choose to take the researcher’s word for it, you’d do well to consider the limitations of this study.

The major limitation is that the sample size was relatively small, with the participants being mostly young, healthy, and heterosexual men. Thus, whether you can generalize these findings to other population groups, such as women, older adults, or people with different sexual orientations, is not clear.

Secondly, this study used only one type of emotional tears, i.e. tears induced while watching sad movies. It is possible that tears elicited by other emotions, such as anger, fear, or happiness, may have different effects on aggression or other behaviours.

Thirdly, the study only measured a single aspect of aggression, i.e. the willingness to inflict noise on another person. It is unknown whether tears would have similar effects on other forms of aggression, such as physical violence, verbal abuse, or cyberbullying.

The study also did not examine the underlying molecular or neural mechanisms of the tear-chemosignal, such as its chemical composition, its binding affinity to the olfactory receptors, or its modulation of neurotransmitters or hormones. These are important questions that will perhaps be tackled and thus answered in future research.

(Image Credit: Image generated using AI on Lexica.art)

WHAT OTHER STUDIES SAY:

What is interesting, is that past studies about tears and human behaviours have come up with similar results. Another 2011 study from the same Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot, Israel, that did this study, found that the smell of a woman’s tears collected when she was crying has the power to reduce a man’s sexual arousal. The men in this study never saw anyone cry, and they had no idea, as they were examined using MRS – magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Yet, researchers found that their testosterone levels were reduced and so were those parts of their brains involved in sexual desire.

The researchers hypothesized that these odourless chemical signals in the tears may indicate sexual unavailability or distress as a way of preventing or resolving conflicts, similar to what they observed in rodents.

(Image Credit: IEDB)

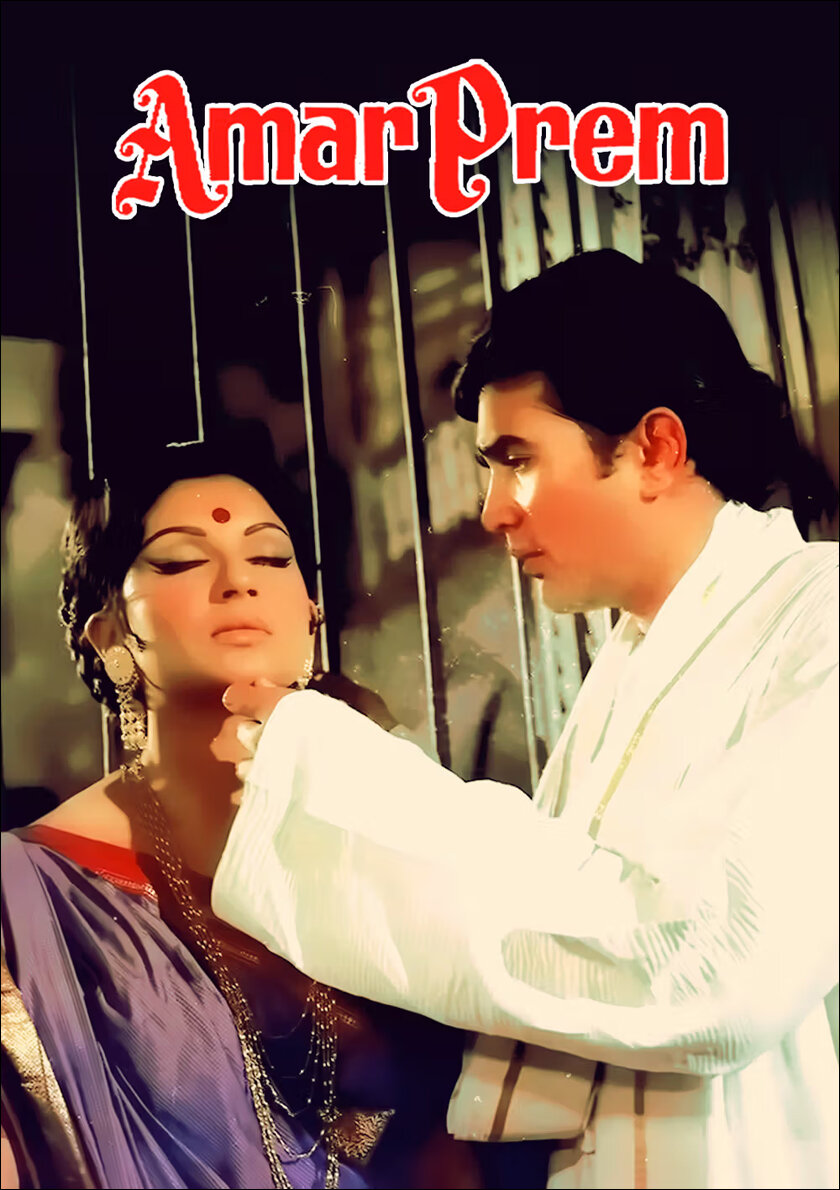

I HATE TEARS, PUSHPA:

In film after film, we have seen characters talking down tears. Rajesh Khanna, in one of cinema’s most memorable lines, says, “Pushpa, I hate tears.” In others, we have seen men berating women for crying during times of conflict. But as this research suggests crying not only reduces men’s aggression, there are other studies which talk about the benefits of crying.

One research found if the crier receives social support or resolves the problem that caused the tears in the first place, the crying can improve mood. Another found that crying can reduce pain – both emotional and physical, by releasing endorphins and oxytocin, which are natural painkillers and stress relievers. Crying can also lower blood pressure and heart rate, which can have positive effects on health.

Another found that crying can enhance memory, especially for emotional events by increasing arousal, attention, and emotional processing, which are important for memory formation and consolidation. Yet another study concluded that crying may influence perception by activating the mirror neuron system, which is involved in empathy and emotion recognition.

In 2010, Zoya defended her crying. She need not have. Films are engines of emotion. If this research is anything to go by, perhaps the Zoya of 2024, will instead demand that her crew be quick to shed tears. Besides bettering life, tears might also have the power to better films.

In case you missed:

- AI Adoption is useless if person using it is dumb; productivity doubles for smart humans

- Copy Of A Copy: Content Generated By AI, Threat To AI Itself

- India’s Upcoming Storm of AI Nudes & Inspiring Story Of A Teen Warrior

- Prizes for Research Using AI: Blasphemy or Nobel Academy’s Genius

- How Old Are We: Shocking New Finding Upends History of Our Species

- You’ll Never Guess What’s Inside NVIDIA’s Latest AI Breakthrough

- Quantum Leaps in Science: AI as the Assembly Line of Discovery

- Rogue AI on the Loose: Can Auditing Uncover Hidden Agendas on Time?

- OpenAI’s Secret Project Strawberry Points to Last AI Hurdle: Reasoning

- The Path to AGI is Through AMIs Connected by APIs