Generative AI so far has depended on AI companies illegally scraping data off the net including copyrighted ones writes Satyen K. Bordoloi as he highlights both sides of lawsuits that can define the future of AI and human progress.

“There is nothing to writing. All you do is sit down at a typewriter and bleed,” said Ernest Hemingway. Ask ChatGPT to write in Hemingway’s style and it will do so within seconds. So, like Hemingway bled (literally as well) to gain the experiences that made his writing deep – how much did ChatGPT bleed to churn out a copy?

This is at the heart of one of the most contentious debates about technology, one that will decide the fate of the most useful technology we have made – Artificial Intelligence. 2023 saw multiple lawsuits filed against almost every generative AI (GenAI) company for their habit of scraping data from the internet without consent to both train their AI models and have them generate content.

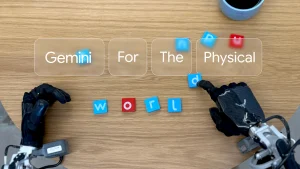

(Image Credit: Writer’s Lawsuit)

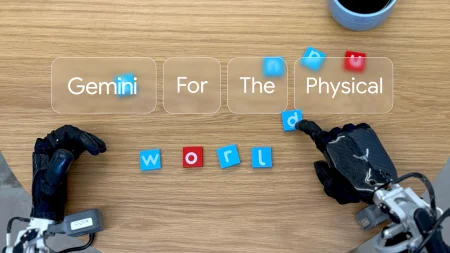

The most famous is a class-action lawsuit filed by some of the most famous writers and publishers against OpenAI and Microsoft. The accusation is that these companies illegally used these authors’ and publishers’ copyrighted works to train their AI products like ChatGPT, DALL-E, and Vall-E. It’s filed by some of the most famous authors including John Grisham, George R.R. Martin, Jodi Picoult, and David Baldacci with the Authors Guild and several publishing houses. The accusation is that the defendants violated their rights by scraping their books, articles, and journals from the internet, without consent, compensation, or attribution.

“These algorithms are at the heart of Defendants’ massive commercial enterprise,” the suit states, adding, “And at the heart of these algorithms is systematic theft on a mass scale.” The plaintiffs allege OpenAI is making them “unwilling accomplices in their own replacement” and argues that the AI products that can generate text, images, and videos based on user prompts, are creating derivative works that infringe upon their original works and compete with their market. They also allege that these actions have harmed their reputation, privacy, and creative control and are seeking a permanent injunction to stop them from using their works, as well as damages and disgorgement of profits and want defendants to disclose how they obtained and used their works, and to delete or destroy any copies of their works in their possession.

This one-of-a-kind lawsuit – one among dozens – can upend a world order being created using GenAI and threatens to put a stop to a technology that is reshaping everything about our world faster than we can comprehend it.

WHAT IS DATA SCRAPING:

Data scraping is a process by which AI companies collect vast amounts of data from the internet and use it to train their AI models. This can be text, images, code, and other types of information. The more of that an AI system has to train on, the better it is at performing tasks.

Data is the new oil. Data scraping is the process of mining for that oil in the vast ground that is the internet. This is both mining and sweeping everything they come across, copying it and keeping it to train and use on their AI models. The only problem is that you’re mining in others’ backyards without their consent or compensation. What it is used for, has the world gasping in wonder.

It is this data that allows machine learning models to answer questions in such a comprehensive and informative way that it leads people to wonder if they are having conversations with another human. They are used to train all kinds of AI models besides those that generate text, images, videos and codes and include those that can drive cars, chatbots, fraud detection programs etc.

As the lawsuit outlines, no consent was taken from creators of these writers, artists, coders etc. Texts created by you and me, including articles like this one and your social media posts – are also part of GenAI data sets. The practices of these AI companies are opaque – OpenAI is open only in name – and their data scraping policies, procedures, practices and uses are not at all clear.

(Image Credit: Ernest Hemingway Photograph Collection, Kennedy Library)

Ernest Hemingway literally bled – taking shrapnel wounds during World War I, surviving other injuries including from two plane crashes, on the path to the experiences from which he wrote what he did. But a generative AI like ChatGPT fed on all his books can write like Hemingway within seconds. How is this fair, the plaintiff would ask?

The problems from scraping data are obvious, but the necessity of it – not so much.

WHY SCRAPING DATA HAS NO IMMEDIATE SUBSTITUTE:

Every AI model – not having context or meaning of its own – requires a vast amount of data to train them to do what they do. This is necessary not just so you can serenade your lover with a sonnet in the style of Shakespeare, but also to find protein structures, maybe solve climate change, find cures for cancers, etc.

Scraping data off the net is feasible for startup AI companies struggling with funding, as it is cheap and a vast amount of data can be collected quickly and easily. The data also has variety as it includes not just websites and social media posts, but also public records and works created by writers, poets, painters, photographers, coders etc. These are data impossible to collect manually, and putting restrictions on them would impede the development of this technology.

IN DEFENCE OF DATA SCRAPING:

Think of how generative AI works. It is fed all kinds of data available scraped from the net, has to be trained by hundreds to thousands of people and once this mass production of logic is done, it can churn out whatever you want based on your prompts while guzzling a lot of resources, both during training and generating responses.

Generative AI – in essence – is a socialist tool, that needs capitalist deep pockets to run. And that is a problem. In restricting the AI industry right now, we run the risk of bankrupting the entire generative AI industry even before it’s begun in earnest.

Secondly, what these systems are doing, is recognize patterns in data. Thus, while Hemingway’s style is unique, writers across the ages – including me – have tried to read his works and understand how he writes, and decode his pattern which is pithy, short sentences without difficult words. The difficulty is in the strength of the emotions he conveys, not the words he uses. Similar patterns of writing, or making images or photography, can be found in the work of every artist and creator. And if there is one thing AI is fantastic at, it’s pattern recognition.

Hence, while the method of scraping data can be questioned, are these systems pattern recognition also such a big problem? The style of a writer is nothing but the way she does things over a lifetime of practice. That this pattern can be copied, once understood, does not take away from the work that has been created. I may write in the style of Hemingway after analysing his patterns. But what I create from trying to copy that style, would that be mine or Hemingway’s?

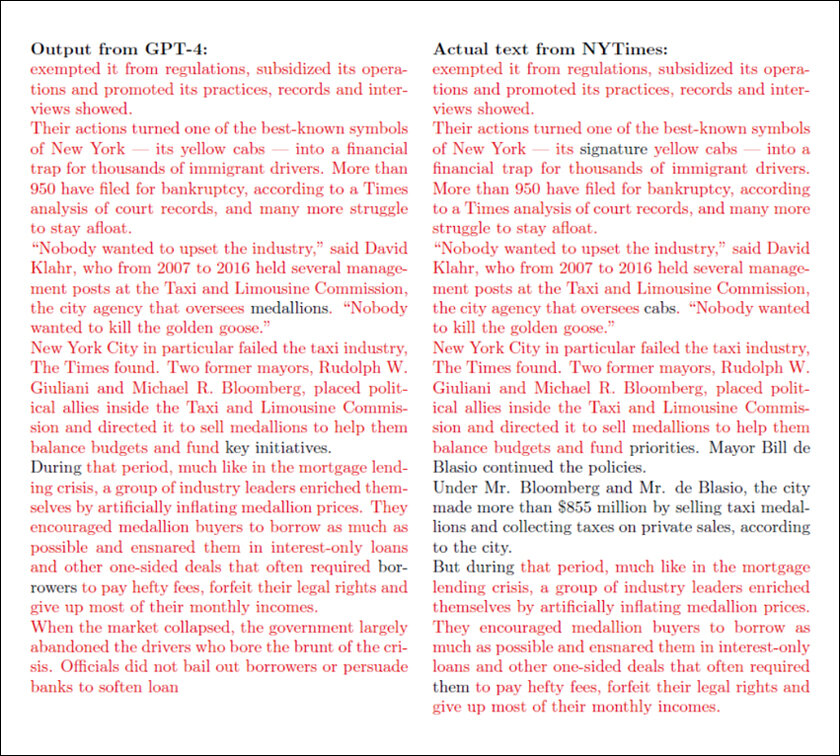

In the same vein, if a ChatGPT does the same – write in the style of Hemingway – as long as it is not copying long passages of data as it did for New York Times articles as their lawsuit highlights – should Hemingway have a problem?

I am not negating the side of the writers and creators. As a writer myself, I understand the issue and can benefit from the lawsuit. But I am also a science and technology writer who has spent a decade trying to understand AI and written extensively on it. Hence, I realise that considering the other side is also important. That’s also because this lawsuit is only the start.

So far, generative AI can copy the styles of painters, photographers, writers and coders. But feed 20 papers on a topic and tell the generative AI to come out with an idea from it. If trained well, the GenAI would do so. Who would own the copyright to that idea? What if it is a cure for an incurable disease that can be worth hundreds of billions of dollars? Should the GenAI company own a bit of the rights to that idea, considering their effective training led to it? Or should such life-changing ideas, or any ideas created by AI, be copy-left?

The next lawsuit would be by production houses. Video generation AI tools are becoming better. Ask one to create a clip in the style of Wes Anderson movies, and it’ll do so in moments. So, can Wes claim copyright infringement on style and demand to know how they got hold of a copy of his work? Would it be okay if the generative AI companies pay Wes, or any writers or publishers, to own legal copies of their works to be fed into the systems? How would we determine the payments – GenAI works in bulk and the qualitative aspects of the writers matter less than the quantitative bits of it. Would we have these GenAI companies pay creators only if a user specifically asks to create work in someone’s style?

As you can see, there is no end to the pandora’s box of questions that GenAI opens up and which will have profound implications for the future of our species and the planet. It is easy to take sides. But before we do, let us remember none other than the veritable Hemingway who had an important thing to say about the matter: “I know now that there is no one thing that is true – it is all true.”

In case you missed:

- Copy Of A Copy: Content Generated By AI, Threat To AI Itself

- How Lionsgate-Runway Deal Will Transform Both Cinema & AI

- Are Hallucinations Good For AI? Maybe Not, But They’re Great For Humans

- The Great Data Famine: How AI Ate the Internet (And What’s Next)

- OpenAI’s Secret Project Strawberry Points to Last AI Hurdle: Reasoning

- AI vs. Metaverse & Crypto: Has AI hype lived up to expectations

- Rethinking AI Research: Shifting Focus Towards Human-Level Intelligence

- AI as PM or President? These three AI candidates ignite debate

- DeepSeek not the only Chinese model to upset AI-pple cart; here’s dozen more

- A Manhattan Project for AI? Here’s Why That’s Missing the Point