Sairaj Iyer speaks with experts and writes on a once-innovative engine that may have crashed the aspirations of an airliner.

May saw two events dent consumer confidence in the aviation sector.

On 25th May, the British Airlines website crashed keeping customers off information about their travel schedules. Website tracker Downdetector.com reported users complaining disruption in the application and website.

A similar phenomenon played 4,000 miles away in India in the first week of May. Several customers waited for refunds on tickets booked with GoFirst Airlines. What baffled everyone was the airliner’s decision of approaching the NCLT (National Company Law Tribunal) citing bankruptcy.

In the legal case, GoFirst has complained of how Pratt and Whitney’s engines left it with no option but to seek legal recourse. To the average aviation passenger, every adverse event with an airline plays out like the scene from the Salman Khan starrer movie Maine Pyaar Kyun Kiya.

Remember the scene where Sushmita Sen laughs off Arshad Warsi’s premonition that the plane she has boarded did not have Macwheels? A frightened Arbaaz Khan who has overheard a part of Sen’s conversation abruptly deboards that plane. A similar scene is enacted in Friends where Phoebe asks Rachel to get off the plane. Reason? An issue with the left Phalange.

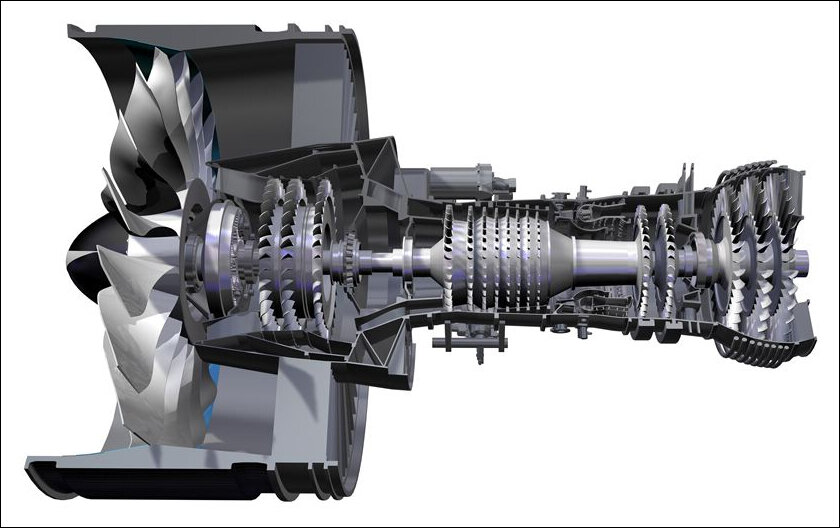

Planes have neither Macwheels nor phalanges. But they do have engines. And the Pratt and Whitney (PW) Geared Turbofan (GTF) engine flying GoFirst’s leased A320neos were marketed as innovative. To evaluate PW’s revolutionary GTF technology and its efficiencies, one may have to understand how aviation engines work.

Revolutionary & Innovative GTF Technology?

Conventional engines on a plane are two components – a fan blade at the front, and a turbine towards the rear. Both these components operate at the same speed. Thrust in an aircraft would be produced by pushing air through a turbine to move the engine. Although this design has been in fashion since 1930s when turbines were fixed to engines, it was not a fuel-efficient process.

By 1993, PW had started a working model where the front fan and the rear turbine could run at different speeds thanks to a gear-control. In 2008, Pratt and Whitney announced that its innovation would be tested on a Boeing 747. A company press release subsequently claimed that the engine was put to test – 40 hours in phase one and 75 hours in phase two. Also announced was this engine to be put in service by 2013.

It was revolutionary because differential speeds between the fan and turbine improved efficiency. Pratt and Whitney claimed 12 to 15% fuel-efficiency. Besides, PW also claimed that its engines were silent by 31 decibels and reduced CO2 emissions significantly.

Resemblance to Segway

The number of reports and media briefings between 2008-14 referring to PW’s engines as innovative is countless. But few of them addressed specifically how it was innovative. Or, proved that the innovation was meant for a long journey. It had the aura of a Segway, a long-forgotten product from 2012, which was marketed as innovative and claimed to redefine consumer mobility market.

Segway had the first mover in the electric vehicles category. Steve Jobs predicted it to be as big as a PC and Jeff Bezos too excitedly rode a Segway in 2002. But despite testimonies, Segway could not sustain it. Analysts had a volley of questions waiting to be answered – pricing, the excessive weight, and the efficiency of the one USP Segway claimed – self-driving.

By 2008, all the excitement around Segway had been lost and soon it was sold off to James Heselden, a genius and a hero who gave the US army the Hesco Bastion. Unfortunately, Heselden died in 2010 from injuries he sustained falling off a cliff while riding a Segway. The early criticism of PW’s engineering has come from Qatar Airways who questioned the efficiency of the engine in dry climate of Qatar which reaches 45 Celsius during the summers. The only difference with Segway was how PW’s R&D and communication teams consistently re-engineered solutions.

Qatar Airways was a major prospect for PW, but the airliner walked off from a deal citing technical issues. That was as early as 2010. Some of the issues reported back then were the zero demonstration of 20% lower maintenance costs and failure to demonstrate fuel-savings. By 2013, the PW1000G had three variants, latest being the PW1100G-JM. In its third iteration, the PW engine did not maintain desired temperature resulting in engineers redesigning a nozzle.

Qatar Airways had also expressed in 2016 about PW technology not being adequately tested. Its CEO Akbar Al Baker was cited in this article as saying, “I don’t think this engine was tested adequately, especially for the temperatures in which Qatar Airways will operate.”

Regulation & Extending Deadlines in India

Despite negative reports, Indian airliners had paid little heed to what Qatar Airways had clearly communicated. But by 2017, engine-issues in India had turned into an open secret. That year, IndiGo asked pilots of its A320Neo models to fly at a lower altitude of 30,000 feet as opposed to 36,000 feet. This fix was recommended by PW to reduce the strain on the engine. Another report recounts how a pilot averted a major mishap mid-air and called the engine performance as “sluggish“.

By the end of 2017, reports of oil-seal issues started cropping up. This time, a knife-edge compressor seal caused unwanted vibrations. Subsequently, the European Union Safety Agency (EASA) instructed airliners to ground A320neos with two PW engines of a certain type. DGCA, the Indian regulator too passed an order in 2018 asking airliners (IndiGo and GoFirst) to ground Airbus planes powered by PW engines.

Clearly the regulator was lenient towards the airliners who cited supply-chain worries. The regulator may have also been lenient keeping in view the coronavirus pandemic. IndiGo’s compliance was communicated a few days before the penultimate deadline of August 31, 2020. It was quite a remarkable feat considering IndiGo replaced engines off 106 of its fleet of planes. But GoFirst? They still had not complied.

It seemed as if GoFirst was waiting for PW’s assistance. And why not, replacing engines is a costly proposition and PW had made two tall announcements between 2018-20. First, PW claimed of having found a robust solution to improving efficiency of the low-pressure turbines. This tweak would be applied starting from June 2019. Second, PW claimed of building an MRO (Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul) facility in Mumbai through a partnership with Air India Engineering Services Limited. Unfortunately, neither of these worked for GoFirst.

Support Worries

PW roped in AIESL, the over fifty-year old MRO, to offer support services and reduce systemic worries. An AIESL official on condition of anonymity confirmed the project. “Initially Pratt and Whitney would provide training to our engineers. Subsequently, facilities at AIESL were to be expanded. But the pandemic and lockdown restrictions hampered our plans,” explained the source.

What also did not work in GoFirst’s favour were costly engine components which had to be often imported. The source explained, “The technology had critical challenges. There were abnormal heating issues with the engine. With most GTF models, there were gearbox issues. There were also issues with sourcing and procurement of components.”

What surprised observers is the paradox between IndiGo and GoFirst. They had the same problem but a different end-result. Several media reports claimed that it may have been owing to IndiGo’s specific agreements on compensation in the likelihood of delays. But the lockdowns have received equal blame given how GoFirst’s worries got accentuated right after the pandemic.

Engineering Worries

Pulak Sen, an aviation enthusiast, and the Founder-Secretary General of the MRO Association of India narrated of the engineering worries with PW. “Lighter engines were designed for narrow bodies like the A320neo. But the materials were not tested and resulted in frequent breakdown.”

Sen’s thoughts echo what one gets to observe in the international aviation market. Although significant efficiencies were marketed, the average life of engines has drastically gone down. Iraqi Airways, for example, received a notice to discontinue its services with immediate effect on May 2nd, 2023. This airliner claimed its planes had served for barely two years. The average life of an aircraft engine is about 15 to 20 years.

PW’s worries in America have been equally well documented. In 2021, a United Airlines Boeing 777 made an urgent landing after the engine caught fire. In a separate incident in Japan, a flight had to return quickly after take-off over a technical snag. Swiss airliner Lufthansa too has complained of PW engine-worries in its fleet. In fact, a NYTimes article reported how the US Federal Aviation Administration was increasing the inspection of PW powered aircraft. The report also cites issues with fractured fan blades and the need for an analytical tool to check for integrity prior to take-off.

To give credit to PW in India, the engine-maker achieved the distinction of two million flight hours as of December 2020. But it was late considering IndiGo by then had already replaced its engines and GoFirst was delayed in meeting DGCA’s regulatory compliance.

Explaining the technology, Sen added, “the materials in the engine such as the hot and cold parts have not been able to withstand heat. Also, less than 1,000 hours of test-flying experience is insufficient to put engines into operation.”

Engine worries have been reported across manufacturers, and Sen explained, “It is not the first time that we are discussing engine issues. Such issues were reported with LEAP engines as well. But in most cases, manufacturers have offered good support services.”

We also asked our sources if India could build engines domestically to meet its demands for commercial aviation. One source explains, “It is early for an engine-manufacturing or even assembly-line. Besides trade secrets, there are intricate aspects around design, manufacturing, and even metallurgy that we would have to sort out first.”

French Economist Frederic Bastiat’s concept of ‘The Seen and the Unseen‘ is an apt way to scrutinize innovation. In the case of PW, positive factors such as fuel-efficiency and lower emissions were ‘Seen’ and communicated. But the ‘Unseen’ effects such as lower age of engines, and disruptions were oblivious. That despite airliners such as Qatar Airways clearly commenting their distrust.

If GoFirst perishes, it will be India’s 70th airliner to fail. The industry hopes that it survives, and this incident serves as a wake-up call to every CXO planning to buy any technology.

2 Comments

Good

Technlogy salesmn is saling technlogy but no suport. Sad!